Have you been watching Orphan Black? I have, and enjoying it immensely as a way to get away from writing up my PhD. Unfortunately, though, the fact that my thesis is all about performance makes it pretty much impossible to ignore my research completely when watching a TV series. Especially this one. I can’t help but use eighteenth-century methods to reflect on the program’s plot, its mise en scène, or, in the case of Orphan Black, how it depends so heavily on its lead actress (and now producer too) Tatiana Maslany.

Have you been watching Orphan Black? I have, and enjoying it immensely as a way to get away from writing up my PhD. Unfortunately, though, the fact that my thesis is all about performance makes it pretty much impossible to ignore my research completely when watching a TV series. Especially this one. I can’t help but use eighteenth-century methods to reflect on the program’s plot, its mise en scène, or, in the case of Orphan Black, how it depends so heavily on its lead actress (and now producer too) Tatiana Maslany.

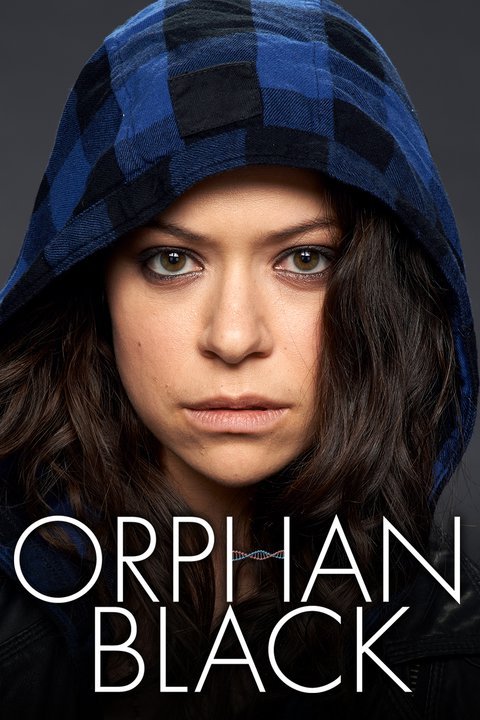

A bit of background is in order here, so prepare yourself for a few spoilers. Orphan Black is set in contemporary North America, with one difference: human cloning was achieved several decades back, and then – with key aspects of the research mysteriously lost – hushed up. All is well until, one day, a woman called Sarah Manning comes across what appears to be her identical twin (but is really her clone) in a train station. From there, a complex series of events unfold, in which Sarah meets (at time of writing) ten other clones, and, together, they try and work out who they are and where they came from.

All the clones are played by Tatiana Maslany. Yet all of them are distinct characters: Sarah is former con artist, Cosima a geek, Alison a soccer mom, Helena a trained assassin, and so on. Maslany’s ability to transform from one person to the other is extraordinary, and has won her numerous acting awards.

What interests me, however, in my own little eighteenth-century way, is how this ability to transform has, to a certain extent, hidden Maslany herself. When watching Orphan Black, unless you try very hard indeed, you do not see the same actress in each of the parts. Televisual trickery sometimes helps with this: by combining several takes, it is possible for multiple clones to meet and talk (and, in one extraordinary season finale, dance) together. Yet even when there is no post-production help, the most critical of viewers will be hard pressed to say that Sarah, Cosima, Alison and all the others are visibly the same person.

Maslany’s ability to enter into each of these roles so completely that it is so hard to see the same actress behind them all is proof of something that was once called “general sensibility”. John Hill coins this term in the 1755 volume of The Actor.

Hill argued that “any particular turn of mind, far from qualifying a person for playing, is rather a disadvantage”. For him, an aspiring actor must instead possess a “ductility of mind”, a “general sensibility”. In other words, “It were best that the heart of the player had no reigning passion of its own” but rather a “ready sensibility of all”. In these circumstances, the actor would disappear into the role assigned to them, as Maslany does in Orphan Black.

Interestingly, Hill is pushed to theorise “general sensibility” as a way of understanding why performances by star actors of his time, like David Garrick and Spranger Barry, sometimes fell short of their full effect, because, as he puts it, “whether we see Mr Garrick in Richard or in Osmyn, still [we see] Mr Garrick”. Only an actress, Susannah Cibber, possesses the full general sensibility that means we do not identify the player from the play.

Perhaps Cibber is an ancestor of Maslany. If not by blood, than at least by intellectual tradition. There is certainly much more to say about Orphan Black with regard to early modern acting theory. For example: the TV series has (spoiler) a series of male clones too, but they – unlike the women – are far less varied. Perhaps the showrunners couldn’t find an actor with enough “general sensibility”?

Another question. If Maslany becomes more famous, will she lose the power to transform? Hill attributes Garrick’s visibility in to a lack of “general sensibility”, but more modern approaches might call this phenomenon a downside of theatrical celebrity. Isn’t an actor’s art also dependent on the eye of the beholder?

And one more thing to finish with. Hill suggests that “general sensibility” entails having “no reigning passion” of one’s own. I feel Maslany might take issue with this: is she really an unfeeling person, oddly characterless when not in front of the cameras? I doubt she’d say so. And then, to step once more into the world of Orphan Black, can we justly distinguish Cosima from Sarah, Helena from Alison, in terms of a “reigning passion”? If so, then where did it come from, given that the characters are all clones of each other? An important, submerged, implication of the premise of this series as a whole, but one that soon appears after a little reflection, is that we are not mere slaves to our genetics, but rather infinitely variable, if not – perhaps – to the extent of Tatiana Maslany and her “general sensibility”.