A cheery subject to start 2014, I know.

I’m going to be giving a lecture at the English Faculty in mid-January (which I’ll probably post a recording of here too), entitled ‘The Death of the Actor: Shakespeare and Tragedy in the Eighteenth Century’. Before writing the whole thing, however, I wanted to sketch my ideas out, and decided that such a sketch would make a good blog post. I’m going to arrange things in three sections, beginning with how actors performed death in the eighteenth century, then talking about why such moments are of interest to me with regard to performance theory of the period. In the last section, I’ll consider how the death of the actor relates to Barthes’s famous essay on the death of the author.

First, then, how did an actor perform death? Before we get to the actor, we should first talk about the stage on which he has to die. The stage was made of wooden boards, and probably quite dirty. In order to protect the actors’ costumes (a theatre’s most valuable assets), a thick carpet was routinely laid over the stage for the actor to die on. This practice of laying the so-called ‘tragic carpet’ fascinates me, but is infuriatingly difficult to find out more information about: how much carpet was used? Did the placement of the carpet clearly indicate where the death-scene would occur, and would there be multiple carpets for multiple deaths? I could go on, but the larger question behind these niggles is whether the tragic carpet was even visible to the audience of the time. By ‘visible’, I mean something more like ‘noticed’: just as the lighting gallery or raised stage curtain are present but unremarked in modern theatres, was the ‘tragic carpet’ so routine a piece of stage property that the audience could still be surprised by the deaths it heralded?

First, then, how did an actor perform death? Before we get to the actor, we should first talk about the stage on which he has to die. The stage was made of wooden boards, and probably quite dirty. In order to protect the actors’ costumes (a theatre’s most valuable assets), a thick carpet was routinely laid over the stage for the actor to die on. This practice of laying the so-called ‘tragic carpet’ fascinates me, but is infuriatingly difficult to find out more information about: how much carpet was used? Did the placement of the carpet clearly indicate where the death-scene would occur, and would there be multiple carpets for multiple deaths? I could go on, but the larger question behind these niggles is whether the tragic carpet was even visible to the audience of the time. By ‘visible’, I mean something more like ‘noticed’: just as the lighting gallery or raised stage curtain are present but unremarked in modern theatres, was the ‘tragic carpet’ so routine a piece of stage property that the audience could still be surprised by the deaths it heralded?

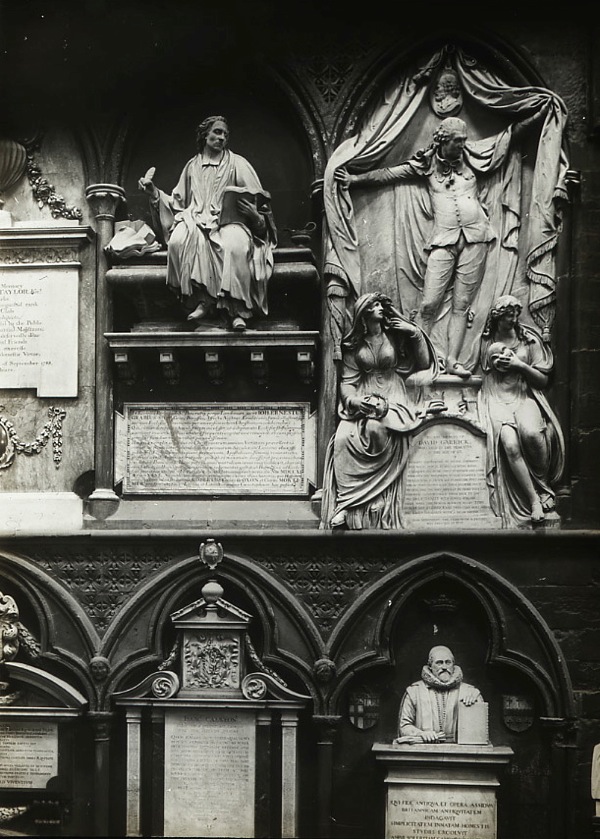

So far, I know only that the carpet was probably set down in the interval preceding the act in which characters were to die, following the entr’acte entertainment. I suspect too, that it was placed near the front of the stage at Drury Lane or Covent Garden, since an actor’s slow collapse upstage would have been difficult to spot due to his necessarily reduced height. Knowing these two things, it is useful to turn to a speech that David Garrick added to Macbeth, intended to be spoken as he, in a departure from the original, succumbed on stage. This speech is long, too long to quote here, but would allow ample time for Garrick to lower himself onto the carpet with great precision. Such a slow death would also give the opportunity for Garrick to employ all the action for which he was so famous: many a dramatic pause or sharp change of tone are possible as illustration to these dying words, as are the changes of skin colour, rosy to pale, that contemporaries reported seeing in his Romeo and Hamlet.

Such death scenes were often the crowning glory of a part. Garrick certainly would not have added one to his Macbeth if such a passage could damage the spectacle. At the same time as being a highlight, however, dying on stage also poses a great many theoretical problems. It is interesting to me, for example, that while most acting manuals talk about love and beauty, I’m yet to find one that tells an actor how to die. This is, I believe, because such manuals are founded on the belief that the best actors are those who can draw on their own experience to inform their action: real-life lovers are meant to be the best at playing the role of lovers, for example. Yet, how can someone have experience of dying? At best, only the outward signs can be copied, with no knowledge of what a person feels at the end of their life to awake the sensibility that is meant to drive the actions of the performer. In the moment of death, therefore, the actor is at his most theatrical: in a positive sense, because this moment offers an opportunity to show off all the nuances of physical action at the performer’s command; but also in a positive sense, because it is a moment that proves the actor performs without feeling what he acts, that his imitation is only skin deep.

A quick aside. From my own theatre experience, I know that an audience’s attention is powerfully drawn to a dead body on the stage. Myself and others cannot help looking to see if the character is still breathing. Of course they are, but still we must look. It is perhaps for this that I can’t immediately think of many Shakespeare plays where the attention is left on a dead body: Hamlet dies, and Fortinbras enters with a fanfare; Lear dies, and Edgar, Kent and Albany step forward to survey the massacre; Othello dies, and Iago must be dealt with. The only two counter-examples are, first, when Falstaff pretends to be dead in Henry IV part I, and, second, when the statue of Hermione comes to life in The Winter’s Tale. In both cases, it is clear that Shakespeare has constructed the scene in a such a way that it only work if the audience obeys its natural inclination and stares at the supposedly dead figure.