What attitude towards the stage does Alexander Pope’s 1725 edition of Shakespeare’s plays evince? That is the question. Answering it turns out to be quite difficult, so this post will be as much about methodology as about tentative conclusions.

As most readers of Pope’s Shakespeare would, I began with the preface, where many differences with Rowe immediately made themselves apparent. With the aim of “extenuat[ing] many faults [of Shakespeare] which are his, and clear[ing] him from the imputation of many which are not”, Pope argues that, since he wrote to earn his living, Shakespeare was bound to please his audience and therefore had to conform with certain aspects of the theatre, such as farce and spectacle, that a more enlightened audience would abhor. On top of this, Pope also points out that Shakespeare also necessarily spent a lot of time with actors, a disreputable class of people whose lowness may well have tarnished Shakespeare’s brilliance. Ever the master of the pithy phrase, Pope sums up the extenuating circumstances for Shakespeare’s faults as follows:

to be obliged to please the lowest of people, and to keep the worst of company

No praise for actors here, nor even Rowe’s indication that Shakespeare may have himself performed (although Pope does reprint the biography verbatim some pages after this). In fact, Pope does not stop at blaming Shakespeare’s apparent faults on the actors and the stage’s connection to fickle public taste, but also lays out how every kind of error found in the early texts of Shakespeare, especially the First Folio, is also the fault of the players. “The additions of trifling and bombast passages” in such editions is a clear sign of the actors’ forcing Shakespeare to write to please the crowd; the disappearance of “beautiful passages” are the result of “lopping, or stretching an Author” for the stage; inconsistent printing of character names has its root in sloppy promptbook copy-texts; misordered scenes are the progeny of a play divided wherever actors “thought fit to make a breach in it”; and “Characters were confounded and mix’d, or two put in one” because of the size of the current company. Last but not least, the ‘player-editors’, Hemminge and Condell, were so ill-suited to their job that it seemed to Pope that “prose from verse they did not know”.

While Pope finishes this preface by excusing the players’ faults as the actions of people who knew no better, being without the contact with finer minds that eighteenth-century performers enjoyed, the overall tone of this text is clear, and it marks a break with Rowe. Whereas Rowe scarcely mentions the theatre or actors of Shakespeare’s time, Pope makes them bear the blame for many errors in Shakespeare. As for Pope’s attitude to contemporary theatre, things are less clear cut. On one hand, he does carry forward most of Rowe’s locators, as well as scene and act divisions (which were inspired by post-restoration practice), but, on the other, he removes the illustrations and some stage directions, so a particular attitude is harder to discern. Given what else is said about actors, though, I’d suspect a vague tendency towards anti-theatricality.

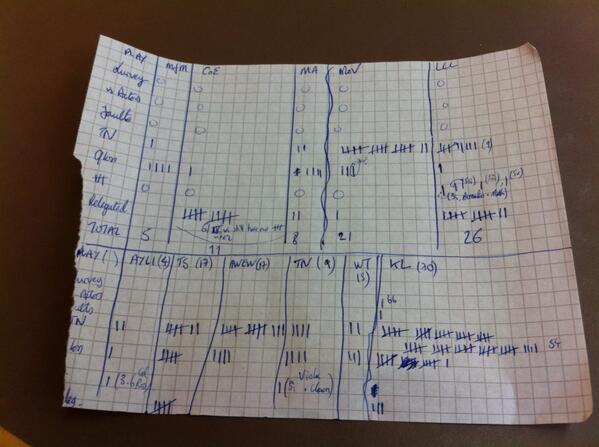

So much for the preface and some aspects of the text. I then turned to the 971 footnotes, with which Pope has adorned these volumes, along with numerous stars and other marginal markings to indicate passages of particular merit or regret. I know that there are 971 footnotes because I have counted them all, dividing them up into categories as I went. I did this in order to grasp the extent to which Pope’s hostility towards the conditions of Shakespeare’s stage was carried over into his notes. Was the attack on the stage confined to the preface or is it continued onto the page of Shakespeare’s plays as well?

Having read all the notes, I can now say that there are only eight notes that criticise actors explicitly. Such notes are scattered through all six volumes, suggesting that Pope was on the lookout for things “interpolated by the Players” throughout his editorial labours. Indeed, when editing Henry V, he actually wishes to have evidence for actors’ involvement in the creation of the ‘English lesson’ scene, as he could then have left it out.

I have left this ridiculous scene as I found it; and am sorry to have no colour left, from any of the editions, to imagine it interpolated.

Against the evidence that Pope’s hostility is found throughout his edition, there is, however, the simple fact that 8 notes on actors out of 971 is not a very high percentage at all, and so such notes and their attitude may easily be lost to the reader. I would argue against this by pointing out that the vast majority of these 971 notes are what I would call ‘textual notes’, pointing out words Pope has emended or insertions made from a different edition than that used for the rest of the playtext. Not only are such ‘textual notes’ often very short and easily ignored (unlike the various rants against actors), but they are also explicitly connected to the errors of actors in the preface: after all, it was the ignorance of the player-editors (at least according to Pope) that have made such textual emendation necessary.

One last point about footnotes and actors. I’ll quote here a long footnote in its entirety, originally found in Julius Caesar during the Plebeians’ responses to Antony’s funeral oration.

* ‘Caesar has had great wrong.

3 Pleb. Caesar had never wrong, but with just cause’.If ever there was such a line written by Shakespear, I shou’d fancy it might have its place here, and very humorously in the character of a Plebeian. One might believe Ben Johnson’s remark was made upon no better credit than some blunder of an actor in speaking that verse near the beginning of the third act,

‘Know Caesar doth not wrong, nor without cause

Will he be satisfy’d‘But the verse as cited by Ben Johnson does not connect with – Will be satisfy’d. Perhpas this play was never printed in Ben Johnson’s time, and so he had nothing to judge by, but as the actor pleas’d to speak it.

This obscure note makes a bit more sense when one recalls that Jonson (in his Timber) criticised Shakespeare’s portrayal of Romans, citing the line “Caesar never had wrong, but with just cause” as evidence. The line, however, not being present in any of Pope’s editions, means that the editor is given free reign to attribute the target of Jonson’s critique to an actor’s ad-libbing. As with the process of extenuating the faults of Shakespeare in the preface, so here in the footnotes do the actors carry the buck as well.

To conclude, I’ll write out a larger idea that struck me as I was wading through notes 700 – 971 of Pope’s edition. The idea was that the figure of the actor was a useful tool, a kind of scapegoat, for the editor, since just the idea of an actor’s meddling in a supposedly correct authorial ur-text augments the options available to the editor. Is this section unsatisfactory? It was probably an actor’s interpolation and can be relegated. Is this passage from a later edition superior to a quarto text? The later text was probably the author’s correction of some player’s error, and therefore the editor must restore the later reading. And so on. The short version of the logic is this: if any part of any text by Shakespeare could have been corrupted by an actor (as Pope makes it out to be), then any part of any text by Shakespeare must be scrutinised by an editor. Ultimately then, the editor builds his authority upon the very nature of Shakespeare’s text as dramatic literature.