One of the greatest pleasures of producing a book has to be the opportunity of discovering how others respond to your ideas. Such pleasures begin long before the book is published, of course, with, in my case, so many coffees and conversations and conference papers. But the process of publication does give some particularly interesting ways of seeing your work reflected back at you. This post is about one of them: the index.

When I asked colleagues about how they prepared indexes to their books, I was surprised to learn that most people said that they did it themselves. I, on the other hand, already knew that I had no intention of doing this: my duties as admissions officer during the pandemic left no time for indexing, and, above all, I decided I wanted a different kind of guide to my book than any I could give (and, indeed, I’d already given one in the last few pages of my introduction). So I turned to the few people I knew who had commissioned indexers for advice and recommendations, and eventually hired, with funding from my university, Tanya Izzard.

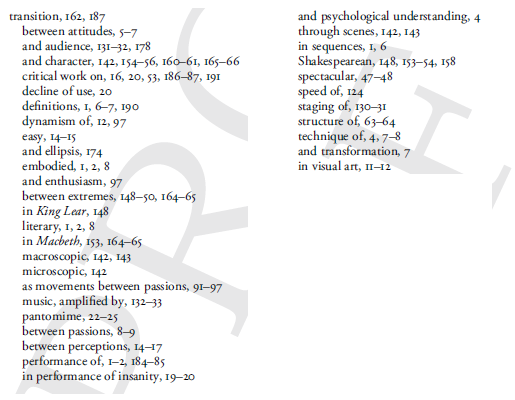

She did an amazing job, and I would recommend her work to anyone. To illustrate a little of what an index can do, I thought I’d talk about one piece of her work:

This is the index entry for ‘transition’, and so for the concept right at the heart of my book. When I first saw this entry, I was a bit concerned at how short it was, given that I talk about transition a great deal in this volume. But then I looked closer, and thought about what a good index should do.

An excellent index need not be totally exhaustive, because, if it were, it might lead to a very weird way of reading my book, where, instead of encountering every point I make about transition (some of them repetitive) in sequence and in their proper context (which gives meaning to the repetition), a reader would lose some of my argument. Instead of such an exhaustive approach, this index provides something very fine indeed: it provides a third person’s judgment of each of the key points I make about transition in this book, and in the places where I make them most cleanly. Seen in those terms, I’m rather proud of the fact that there are still this many entries for transition, since it indicates that, despite what one peer reviewer called my ‘laser focus’ on this term, I still make a range of points about it.

Of course, I could have used my own judgment to produce a similarly constructed index, but I’m pretty sure that I would have been far too close to my book and its material to do so as well as my indexer did. Not only, then, is an index an opportunity to see your work reflected in another, it was also, for me at least, a chance to learn by letting go of my research a little and entrusting it to another.

My book, Criticism, Performance, and the Passions: The Art of Transition was published in March 2021 by Cambridge University Press. You can order it direct from the press, with a 20% discount, by using the code SMITH2021.