Now this is a topic I’ve been thinking about a lot recently, since everything I read to do with acting seems to have something to do with it. Sticotti, about whom I just spoke at the Early Modern French seminar, argues, for instance, that both actors and authors need to have felt (or be feeling) love in order to create the roles of lovers (i.e. perform or write them respectively). Similarly, John Hill and Sainte-Albine both write that only people in love or “of an amorous disposition” should act the parts of lovers. With respect to the relationship between authors and love, Shakespeare himself has Theseus proclaim that “The lunatic, the lover and the poet / Are of imagination all compact” in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and, in As You Like It, Touchstone inform Audrey that “the truest poetry is the most feigning; and lovers are given to poetry, and what they swear in poetry may be said as lovers they do feign.”

So, love unites the poet and the player, since both can work wonders under its influence. Of course, such consensus is far from universal, and the clearest break from it is to be found in Diderot’s Paradoxe, where he has Premier hypothesise that the best love-scenes are performed by people without feelings for each other, since it allows them to render the feelings of their characters better, their own not getting in the way. This fits with what Diderot describes as the ideal state for an actor to be in when conceiving his part (forgive my rough translation: ‘stroke’ renders ‘trait‘):

It is not in the rush of the first attempt that characteristic strokes present themselves, it is rather in those cold and tranquil moments, in moments completely unexpected. We don’t know where such strokes come from: they look like inspiration. It is when, suspended between nature and their draft of it, that these genii [i.e. great actors], look from one to the other; inspiration’s beauties, the fortuitous strokes that they put in to their works and whose sudden appearance surprise them themselves, have an effect and a success quite differently guaranteed than those made up in the heat of the moment. It is up to cold-bloodedness to temper the frenzy of enthusiasm.

In such a model, being in love and performing love would be a state of enthusiasm which no coolness of mind could contain. The player should not act in the rush of his own love, remembered or felt in the moment. If we leap forward to the present day, it is rare for any TV, cinema or theatre audience to believe that the actors they see performing lovers to muse on whether they are drawing on the personal experience of love or not. Occasionally, of course, the story of two actors falling in love as they performed together appears, but I’m tempted to point out here that the very fact that this is a newsworthy story at all depends on its rarity and narratological neatness – and that love between celebrities is newsworthy regardless of its context (we don’t hear much about actors hating each other after performing each others’ enemies).

If acting and love can be, and has been, thought of in such a way, my question in this post is why we don’t think of writing poetry like this? Why does it seem strange to propose that a writer might write of love without personal experience? After all, even Wordsworth, who, with regard to poets, famously wrote something very similar to Diderot’s thoughts about actors’ need for tranquility, actually edges away from the idea of composition without at least some version of corresponding emotion. The passage I’m thinking of is in the ‘Preface’ to the Lyrical Ballads.

I have said that poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind.

Why can we not write poetry without emotion, a love poem without the feeling of love?

This is, or at least feels like, a horrible, terrible question. I’m curious as to why. Lurking here – in Diderot and in Wordsworth – is the deeper question of where inspiration comes from, and the relationship between inspiration and experience. We might, for example, divide the content of all works of art (this is deliberately fuzzy definition) into those things that we do not need direct experience to write about (i.e. nineteenth-century gold-digging in New Zealand, the topic of my current bedside novel) and those that we do (i.e. love). How, then, do we define the line that this distinction draws? It would be tempting to say that writers require direct experience of the emotions they depict and not of the material existence. Unfortunately, there are no end of counter-examples for this: Shakespeare probably never experienced jealousy on the scale of Othello nor Macbeth’s guilt. I could go on, and perhaps propose (as others have done) that while Shakespeare never felt Macbeth’s guilt or Othello’s jealousy, he did feel guilt and jealousy on a smaller scale and was able to translate this into something of appropriate dimensions for his characters.

So is it just love? Not necessarily: I would say that it is very hard to write of grief without experience of it. One could respond here, though, that grief depends on love for its force so all I’m doing here is finding another way of approaching the same question.

So is it just love? Not necessarily: I would say that it is very hard to write of grief without experience of it. One could respond here, though, that grief depends on love for its force so all I’m doing here is finding another way of approaching the same question.

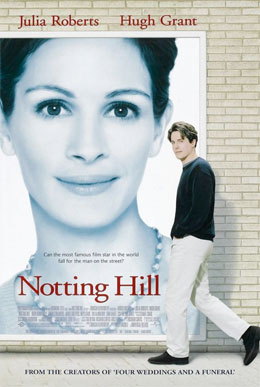

There is no conclusion to this reflection, nor can there be. I’m really only trying to show here – by taking some of my own research as a jumping-off point – that certain kinds of content seem to be felt to require more emotional investment than others. Love, perhaps, most of all. One might say that this is because finding love has become a synonym for finding happiness in our culture. I might resume my entire post by talking then about the film Notting Hill. It is rare audience member indeed who believes that Hugh Grant himself is personally experiencing love as he acts. Rather, what is important is that we want to since that is what is right for his character. How could the bookseller not love Julia Roberts?

One response to “On Love”

[…] belief that the best actors are those who can draw on their own experience to inform their action: real-life lovers are meant to be the best at playing the role of lovers, for example. Yet, how can someone have experience of dying? At best, only the outward signs can be […]